The following is a version of the article I sent out as part of the weekly newsletter for the Churches of Penn and Tylers Green, where I am the Vicar. I have been asked to share it more widely and so am sharing it here as well.

It was written the day of the vote, 29th Novemeber, and sent out the following morning.

A note from the Vicar

This Sunday we are entering into the season of Advent, the beginning of a new liturgical year as we reflect on the birth of Christ and on the ministry he came to accomplish among us. Christmas may be a story filled with joy, such that we sing “Joy to the World”, but Advent rightly understood recognises the pain of waiting, the ache of patient prayer, and the quiet voice of hope which whispers that even on the darkest night the glimmering flame of faith shall not be overcome.

Alas as I write this comment I am mindful that this newsletter’s unintentional delay has afforded me the opportunity to comment on the news of the day; namely that The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill was debated in Parliament and in a vote has moved forward towards becoming a legislative reality.

As a priest there are two fundamental concepts which underlie nearly everything I do in ministry with people: firstly, all are made in the image of God (Genesis 1.27) and because they are made so by their creator - not on the basis of any other characteristic or status or bias - they are to be respected and treated with dignity; second, all have fallen short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23) and yet Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners (1 Timothy 1.15).

Famously John 3:16 says: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.”

The Gospel is good news because the life, death and resurrection fundamentally associates God with all humanity such that no one is excluded or forgotten, offering those who repent of their sins and believe in Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour the opportunity to become more than the image-bearers they already are, but children and heirs of God (John 1.12-13).

The Cross is foundational to the Gospel because it is the central point in all of space and time where the fullness of the human condition encounters the totality of its separation from God in such a way that God experiences our death with us and for us. Jesus does this for us so that he might overcome that estrangement, that he might quite literally bury death and leave it ultimately powerless once and for all.

This is revealed by the resurrection to eternal life, where the same body which was crucified is glorified, is touched and witnessed by the Disciples and many others before he ascends to the right hand of God the Father to live and reign for evermore - even now and today. The Church ever since has held fast to this testimony. Death is no longer the enemy for the Christian because in Christ Jesus we have a gateway into eternal life (John 10.9), a companion who is closer even than our shadow at our right hand (Psalm 121.5), who is our good shepherd; even though we may walk through the valley of the shadow of death we shall not fear for he is with us (Psalm 23.4).

Death is not the end, and for many Christians death (and the days and weeks leading up to it) is an opportunity to witness to our faith; whether we are made martyrs by those that hate the Lord Jesus or whether we are examples to our friends and family, to carers and medical staff who look after us in our weakness, that our faith gives us both a sense of hope and peace.

Yet the reality is that death remains a thoroughly unnatural experience for humans who are created by their God to live. Just because the Christian has hope in the face of death does not mean that death is pleasant. It can be, but this is by no means guaranteed. Indeed, for Jesus it most certainly was not ‘a good’ death.

In recent times I have been asked about the concept of assisted dying, or assisted suicide, and I have responded along these lines: It is often understandable when we hear of individual cases why someone might ask for medical assistance in dying but legislating universally on the basis of individuals is nigh on impossible. When something becomes permissible it becomes viable, and when it becomes viable it becomes practical and therefore at times advisable. To make the pursuit of death permissible leads to making it advisable; no matter what ‘safeguards’ are put in place. This is not the vision of the Gospel when it comes to preserving the dignity and life of those who are made in the image of God and who are loved by God such that for their sake he died for them that they might know, love, and enjoy him for all eternity.

Although the Gospel of Christ as victorious over the grave has ended the power of death to ultimately separate us from God’s eternal presence, the Gospel remains fundamentally about life. The New Testament speaks about life 188 times; by contrast ‘forgiveness’ is mentioned 49 times. Jesus came that we might be forgiven, yes; but his focus is much more on what happens having been forgiven - that we might have life and life to the full (John 10:10).

As such the Church throughout the centuries has always balanced the acceptance of death as a universal reality which comes to us all whilst being fundamentally committed to the principle of loving care and service to those who are sick or in need.

This is why histories of medicine are filled with the histories of monasteries, monks, clergy, and honest Christian men and women whose faith compelled them to tend to the sick and which gave rise to universities and hospitals which laid the groundwork for modern medical science.* All of which has sought to heal and comfort, even when death is inevitable.

One such Christian example is Dame Cicely Saunders, widely recognised as founder of the Hospice Movement. ‘In 1958, shortly after she qualified [as a doctor], she wrote an article arguing for a new approach to the end of life. In it she said, "It appears that many patients feel deserted by their doctors at the end. Ideally the doctor should remain the centre of a team who work together to relieve where they cannot heal, to keep the patient’s own struggle within his compass and to bring hope and consolation to the end."‘

Through her tireless efforts at the hospice she founded, St Christopher's, she was inspirational for the development of modern palliative care and always championed the idea that doctors and others should remain in collaboration with the best care for a person rather than treating them as an issue to be resolved.

Theologically and scripturally as a priest I find myself on this topic overwhelmed by the emphasis of God given life, and equally on the reality that God did not come to erase suffering but to experience and share in our suffering so that we might not be opposed to him but empowered to understand ourselves as being united with him in our suffering. When we open the eyes of our hearts to this message we find ourselves with Paul able to say: “But he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly of my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest upon me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong.” (2 Corinthians 12:9-10)

As a priest, the ordinal (the summary of expectations of the priesthood found in the ordination service) says:

Priests are called to be servants and shepherds among the people to whom they are sent. With their Bishop and fellow ministers, they are to proclaim the word of the Lord and to watch for the signs of God’s new creation. They are to be messengers, watchmen and stewards of the Lord; they are to teach and to admonish, to feed and provide for his family, to search for his children in the wilderness of this world’s temptations, and to guide them through its confusions, that they may be saved through Christ for ever. Formed by the word, they are to call their hearers to repentance and to declare in Christ’s name the absolution and forgiveness of their sins.

With all God’s people, they are to tell the story of God’s love. They are to baptize new disciples in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, and to walk with them in the way of Christ, nurturing them in the faith. They are to unfold the Scriptures, to preach the word in season and out of season, and to declare the mighty acts of God. They are to preside at the Lord’s table and lead his people in worship, offering with them a spiritual sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving. They are to bless the people in God’s name. They are to resist evil, support the weak, defend the poor, and intercede for all in need. They are to minister to the sick and prepare the dying for their death. Guided by the Spirit, they are to discern and foster the gifts of all God’s people, that the whole Church may be built up in unity and faith.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill’s proponents, Labour MP MP Kim Leadbeater and cosponsors such as Amersham and Chesham MP Sarah Green, have repeatedly said that the bill would have appropriate safeguards to protect people and that:

If the bill becomes law it will be illegal, punishable by a sentence of up to 14 years in jail, to:

by dishonesty, coercion or pressure, induce another person to make a declaration, or not to cancel such a declaration;

by dishonesty, coercion or pressure, induce another person to self-administer an approved substance.

(Source: Email from Sarah Green MP to Revd Samuel Thorp, November 28th 2024)

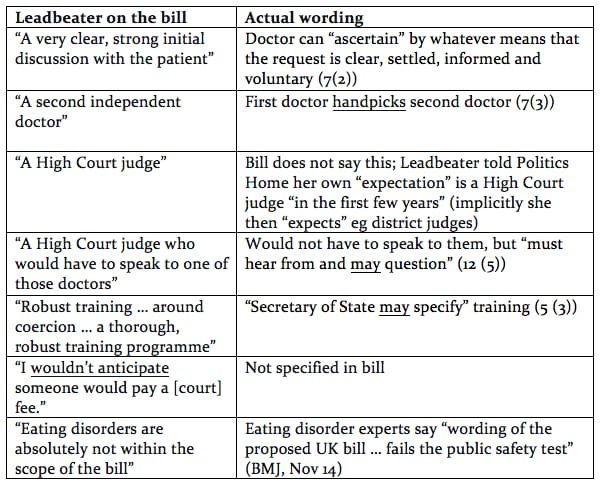

However, the following table raises some concerns about differences between claims made and what the bill actually says:

This is not simply a question as to whether in any specific case an individual might qualify for medical assistance in dying, this is a watershed moment where the entire dynamic of medical care will change from a fundamental presupposition towards the health and well being of the individual to a resolution of practical and logistical issues posed by processes which have to be followed - which may result in the intentional death of the patient.

In countries where assisted dying is already legal we have seen that narrow scopes of what qualifies one for death quickly expand to include other examples. In Canada it was intended that people with severe depression could be eligible for their Medical Assistance in Dying scheme earlier this year. This has been delayed until 2027. It has been observed elsewhere that ‘refusal of treatment’ could be indicative of “a clear, settled and informed wish“ to die. This could be as simple as a diabetic not taking their insulin or someone with an eating disorder refusing to eat.

These issues don’t even touch on the harder to quantify and legislate for secondary realities of external pressures; whether financial, tensions within families, or even culturally through the media. Where there is a narrative that death is a viable option it can become an advised option and this will disproportionately impact the elderly, the lonely, the poor, and the disabled.

In line with our consciences and the ordinal, Revd Graham and I were both signatories along with over a thousand other Church of England clergy, of a letter published in the daily Telegraph asking MPs to oppose this bill. You can read the text of that letter below.

As it happened, on Thursday evening I was at St Margaret’s Parish Rooms for a gathering for people in connection with the Penn and Tylers Green Residents Society where Sarah Green MP was present and we were introduced. I was able to have a conversation with her on this topic and highlighted that I anticipate that if this goes through clergy will find themselves spending a lot of time with bereaved families as they come to terms with their loved one’s decisions and that we will be put in the difficult situation of being asked to be present when people would like to see a priest before ending their lives with medical assistance. That will present a real safeguarding conundrum which I haven’t seen anything discussed about publicly and it seems that there are going to be a lot of unintended consequences that need thinking through carefully. She listened politely, thanked me for offering my perspective and explained briefly her journey to her current position as a co-sponsor of the bill. Although I disagree with her on the issue and how she voted, I did tell her that I appreciated the way she conducted herself in polite disagreement and I hoped that the conversation could be ongoing.

In these two ways I have sought to represent the Christian voice of hope that life and meaning can be found even in the presence of the shadow of death because Jesus Christ is with us and is no stranger to our suffering. This is a message which I hope will encourage you in your own experience of ill health, grief, and the stresses and anxieties the world tries to surround us with.

I’ll end by saying that I have outlined, briefly - believe it or not - my perception of the general Christian position on assisted dying and euthanasia. You may have a different opinion, shaped by whatever factors have led you to it. Please know that if you do have a different opinion I am still your vicar and am here to support you and those you love to the best of my ability, and indeed to the glory of God.

Likewise, If anyone would like to speak with me about this topic, or issues or situations which arise from it, please do feel free to reach out and I’ll be glad to spend time with you.

As we enter into Advent, that time of waiting and trusting God that he will show up and be the light of the world, the source of our hope and joy, I pray that we as a church community will be sensitive to hearing his voice in our lives and that he will open our eyes to the opportunities we have to invite others to encounter his presence, to hear the story of Christmas and to know that whatever their life’s story, whatever their circumstances, their hopes, their fears, their regrets, their shames, their pains, and even their health; there is a God who loves them and dearly desires to know them. A God who at Christmas steps into the world to join them in their story and to invite them to repent and believe in him. A God who in Jesus poses afresh to us the ancient question heard through Moses:

Behold, I hold before you life and blessings, death and curses…

I implore you, choose life.- Deuteronomy 30

With Every Blessing,

Revd Samuel S. Thorp

* I fully recognise that the history of medicine did not begin with the Church and that much is written of practices in not just ancient times but also throughout the centuries, but the role of the Church in the rise of hospitals etc is significant.

I don’t normally ask people to share these notes but if you know people who might find this a helpful reflection on the topic then please do pass it on and along.

Assisted dying clergy letter, published in the Daily Telegraph (Links to PDF)

Signatories - clergy of the Church of England: beneficed, holding a licence, or Permission-to-Officiate.

Signatories include 15 diocesan bishops: the Bishops of Bath & Wells, Birmingham, Blackburn, Chichester, Exeter, Leicester, Lincoln, London, Newcastle, Rochester, Sheffield, Southwark, Southwell & Nottingham, St Edmundsbury & Ipswich, and Winchester.

Sir,

The Private Member’s Bill on assisted dying introduced to the House of Commons on Wednesday 16 October presents a dangerous threat to our society. The Christian faith offers a defence of the dignity of life and a call to improve the quality of life for all those living - including those who are dying.

Proponents of this legislation argue that it is intended only for those acutely suffering at the end of their life; however, in almost all other places where such legislation has been introduced, this provision has been widened over time to remove such safeguards. In the US State of Oregon (oft cited by supporters of assisted dying as a “safe” form of the legislation) the provision has been widened to include non-terminal conditions; in Canada assisted dying for the mentally ill will become legal in 2027; in Belgium assisted dying is now available to children. This is a perilous journey for our legislature to undertake. Not only will assisted dying become more widely available over time, it will also become increasingly acceptable.

This risk applies mostly to those in society who are already vulnerable: the elderly, the poor, the mentally unwell, the long-term sick, the lonely and isolated. The option of death should not be put to anyone in society, least of all those already disadvantaged by a culture that seems to value only productivity and success.

The real answer to these issues is multilayered, but must include greater investment in hospice and palliative care, further medical research into effective pain relief and treatment, and support for the families of those who are dying. These concerns ought to be the urgent concern of our parliamentarians, not legislating to provide an option of death for the suffering.

To reduce the value of human life to physical and mental capacity and wellbeing has sinister implications for how we as a society view those who experience severe physical or mental issues, and risks that those undergoing such suffering come to see their life as of less value than others. Once legislation is made, society itself risks coming to see these lives as of less value, too.

We must resist this culture of death by seeking to improve quality of life for all the living.

Yours etc,

The Revd Richard Bastable (London) author

(Listed: Bishops, retired bishops, and clergy from the Oxford Diocese; including Revd Graham (902) and Revd Samuel (938)).

Rt Revd Mark Ashcroft (Former Bishop of Bolton)

Rt Revd Adam Atkinson (Bishop of Bradwell, Chelmsford)

The Rt Revd Jonathan Baker (Bishop of Fulham, London)

The Revd Desmond Banister (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Michael Beasley (Bishop of Bath & Wells)

The Revd Dan Beesley (Oxford)

The Revd Dr Kirsty Borthwick (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Mark Bryant (Former Bishop of Jarrow)

The Revd Canon Victor Bullock (Oxford)

The Revd Adam Burnham (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Ruth Bushyager (Bishop of Horsham, Chichester)

The Revd Fergus Butler Gallie (Oxford)

The Ven. Jonathan Chaffey (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Christopher Chessun (Bishop of Southwark)

The Revd Fran Childs (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Stephen Conway (Bishop of Lincoln)

The Revd Adam Curtis (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Alastair Cutting (Bishop of Woolwich, Southwark)

The Rt Revd Paul Davies (Bishop of Dorking, Guildford)

The Revd Canon Prof. Andrew Davison (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Jill Duff (Bishop of Lancaster, Blackburn)

The Revd Canon Gary Ecclestone (Oxford)

The Revd Paul Eddy (Oxford)

The Revd Simon Eves (Oxford)

The Revd Chris Ferris (Oxford)

The Revd Thomas Fink-Jensen (Oxford)

The Rt Revd John Ford (Chichester)

The Rt Revd Dr Jonathan Gibbs (Bishop of Rochester)

The Revd Dr Patrick Gilday (Oxford)

The Rt Revd James Grier (Bishop of Plymouth, Exeter)

The Revd Canon Dr Peter Groves (Oxford)

The Revd David Harris (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Mike Harrison (Bishop of Exeter)

The Rt Revd Dr Helen-Ann Hartley (Bishop of Newcastle)

The Revd Preb. Jane Haslam (Oxford)

The Revd Clare Hayns (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Will Hazelwood (Bishop of Lewes, Chichester)

The Rt Revd Barry Hill (Bishop of Whitby, York)

The Rt Revd Michael Hill (Bath & Wells)

The Rt Revd Dr John Hind (Chichester)

The Revd Prof. Joshua Hordern (Oxford)

The Revd Jo Hurst (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Emma Ineson (Bishop of Kensington, London)

The Rt Revd Martyn Jarrett (Southwell & Nottingham)

The Revd Maria Jukes (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Roger Jupp (Southwell & Nottingham)

The Rt Revd Dr Joseph Kennedy (Bishop of Burnley, Blackburn)

The Rt Revd Robert Ladds (Former Bishop of Whitby)

The Revd Canon Dr William Lamb (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Rosemarie Mallett (Bishop of Croydon, Southwark)

The Revd Ian Miller (Oxford)

The Revd Julie Mintern (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Philip Mounstephen (Bishop of Winchester)

The Rt Revd & Rt Hon. Dame Sarah Mullally DBE (Bishop of London)

The Rt Revd Hugh Nelson (Bishop of St Germans, Truro)

The Revd Glenn Nesbitt (Oxford)

The Revd Steve Newbold (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Geoff Pearson (Liverpool)

The Revd Katherine Price (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Stephen Race (Bishop of Beverley, York)

The Rt Revd Nicholas Reade (Chichester)

The Revd Canon Vaughan Roberts (Oxford)

The Recd Alex Ross (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Rob Saner-Haigh (Bishop of Penrith, Carlisle)

The Rt Revd Martin Seeley (Bishop of St Edmundsbury & Ipswich)

The Revd Steve Short (Oxford)

The Revd Joshua Skidmore (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Martyn Snow (Bishop of Leicester)

The Rt Revd Paul Thomas (Bishop of Oswestry, Lichfield)

The Revd Charlie Styles (Oxford)

The Revd Graham Summers (Oxford)

The Revd Malcolm Surman (Oxford)

The Revd Jeremy Tayler (Oxford)

The Revd Samuel Thorp (Oxford)

The Revd Stephen Thorp (Norwich)

The Rt Revd Dr Ric Thorpe (Bishop of Islington, London)

The Rt Revd Dr Graham Tomlin (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Lindsay Urwin (Chichester/Southwark)

The Revd Benjamin Vane (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Michael Volland (Bishop of Birmingham)

The Revd Dr Robert Wainwright (Oxford)

The Revd Canon Dr Robin Ward (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Martin Warner (Bishop of Chichester)

The Revd Andreas Wenzel (Oxford)

The Revd David Whale (Oxford)

The Revd Philippa White (Oxford)

The Rt Revd Dr Pete Wilcox (Bishop of Sheffield)

The Revd Peter Wilkinson (Oxford)

The Rt Revd David Williams (Bishop of Basingstoke, Winchester)

The Rt Revd Paul Williams (Bishop of Southwell & Nottingham)

The Revd Jane Willis (Oxford)